What does it take to be an elite hockey player? Obviously technical ability, tactical intelligence and a good level of fitness are vital components of any good hockey player’s DNA, but there are other, very important qualities that are the difference between mediocrity and excellence.

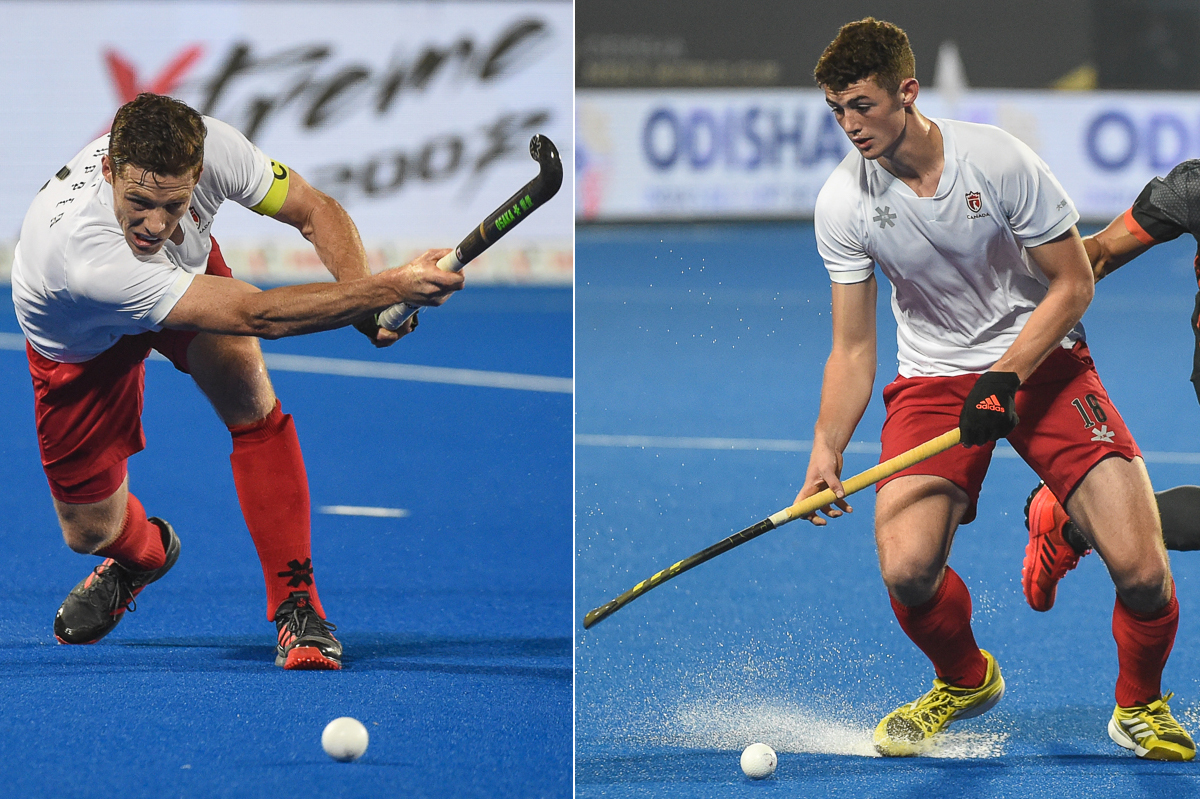

Scott Tupper began playing as a junior international in 2003 and has been a member of the national squad ever since. He has also enjoyed stints playing with some of Europe’s top teams and, even as he approaches 300 caps for his country, his enthusiasm for the day to day life as an athlete remains undiminished.

However, a couple of injuries have persuaded this most competitive of athletes that he might need to re-set his training routine. “It has changed in the last year or so. I have always been a skinny guy but I do love lifting weights but I have had a couple of injuries in the past season that suggest that I have either been unlucky or my body isn’t as able to cope with the stress.

“To counter this, I have had to lower the intensity and workload of my training leading into tournaments. That is a little change I have had to make. I just have to be more conscious about eating well and sleeping well.”

“And,” he adds with a grin, “I am conscious that I cannot engage in as many social activities as I did in my 20s.”

Jamie Wallace is at the other end of the playing scale, with 27 caps to his name, but injuries have been a bug-bear of his too. “From 16 through to 18 I had a pretty big growth spurt and that led to a number of little niggles and injuries. I saw the physiotherapist every week and I developed a very strong foundation in the gym.

“Now, I have grown into my body and so it is about getting stronger without putting on too much weight. I also work constantly on my speed as I am not the quickest over a short distance, so sprint work is an important part of my training.”

It’s not just training that makes athletes successful. In fact, rest and recovery are right up there as essential components of an athlete’s lifestyle. The national program for Canada’s athletes builds in essential rest periods for its players. In fact, for the national squad rest and recovery is mandatory.

“We are told ‘don’t touch your stick’, or we are told not to exercise,” says Tupper. “Then there are other times when we have active recovery, so that is light work, maybe in the pool or on the bike. We have what is called fitness protocols where you might not be active but you are with the team. It is all about taking care of your physiology. It is very important that guys who have had a few days off, maybe to nurse an injury, are brought back at the right intensity so they don’t get instantly injured.”

There is also the question of managing commitments to club as well as country. National team players regularly join European clubs, whose intense league season can take its toll. It is a scenario Tupper knows well as he spent several seasons playing for top clubs in Germany and Belgium: “For the guys who are playing in Europe as well, it is important that a rest period is built in because club and national commitments can take their toll.”

While the national program sets certain fitness training sessions in place, all players are expected to take responsibility for developing their own targeted areas for work away from the group. As Wallace points out, there is always room to improve, whether that is speed, strength, flexibility.

When it is competition time however, the group goes into a different mode altogether. This interview was carried out the day after Canada’s second match at the FIH Series Finals in Kuala Lumpur. The athletes had suffered a first match defeat at the hands of Wales but bounced back to win the second match against a combative Austrian team. The conditions were energy sapping, with temperatures in the high thirties [degrees centigrade] and humidity levels extremely high. Both games had been played at a high tempo and it is true to say Tupper and Waller looked exhausted.

“I will spend most of today off my feet,” said Tupper. “I may watch a movie in my room. Some of the guys might go to the Mall across the way to watch The Avengers that is out in the cinema. The thing is, we might be tempted to explore, particularly in a cool city like Kuala Lumpur, with its markets and so on, but it is extra time on your feet and we can’t afford that. It is good to catch up on sleep and regain some energy. For me, it will be drinking coffee, rehydrating with plenty of water and just getting ready for the next game.”

Prior to travelling out to Malaysia, the Canada team had taken as many steps as possible to prepare for the hot and humid conditions. This year, they had played in Malaysia in the Sultan Azlan Shah Cup, so had experienced the Malaysian climate but, as Wallace explains, the coaches had their own ways of recreating Malaysia’s climate in a cold Canada.

“Back home, at training, we would wear six or seven layers with a garbage bin layer underneath in an attempt to simulate the conditions here. We would also hop in our cars after training and go to a sauna or do hot yoga. Those were the things that we were doing to get our bodies ready for the heat.”

Then there is the mental preparation.

The national team have started working with former national ice-hockey player Chris Beech, who now teaches mindfulness as a means of improving athletic performance.

Beech works with the Canadian players on breathing techniques, relaxation and visualisation. For Tupper, this means listening to a relaxing audio prior to a match so that he is in a calm state when he gets onto the pitch. Some of the players use the techniques to relax after a game, others use it on a daily basis. Again, the onus is on the athletes to take responsibility for their preparations.

One area of team and individual preparation that has changed dramatically in recent years is the use of technology to both gain information on the opposition and to help players improve their own performance.

“Technology has changed a lot since I started,” says Tupper. “In 2003, you would literally walk into a room and watch a video with the coach. Now every guy has clips sent to their phone. Before each game we have 10 or so videos either on our own game or on the opposition.”

The coaches use the video clips in a number of ways. Some video clips are relevant to the whole team: how an opposition sets up an attacking press; others are focused on more specific areas, relevant to just a sub-group of players. Yet other clips might focus on an individuals’s performance in certain situations, for example, for a player involved in a shoot-out, how the opposition’s goalkeeper might react in a one-on-one situation.

“You can get a good discussion going from a clip,” says Tupper. “You might get two or three guys with a different opinion on how a play started or how we could have handled it differently, so you get good conversation between the group about what our solution can be. We tend to watch clips on our own, then we join the group and have discussion and hear other people’s viewpoint.”

Talking to the two athletes ahead of their next FIH Series Final game, one thing is very clear; no matter what age the athlete, being an elite hockey player is not a job, it is a tough and uncompromising lifestyle.