If an American hockey nation were to win Olympic gold in 2016, then it could rightly be hailed as a case of hockey returning to its earliest roots.

While there is no doubt that the modern game of field hockey derived from the English public school system of the 19th century hockey, and its many forms of the game, can be traced back to the earliest civilisations – Greek, Arabs, Persians, Eygptians and the various indigenous tribes of North and South America and the Aztec Indians of Mexico.

Certainly there is evidence in cave drawings, and with the discovery of ancient artefacts, that hockey existed in one form or another more than 4000 years ago, although how close it was to our modern game is something that is forever lost to the mists of time. The first evidence of an organised form of the game can be seen on an Egyptian bas-relief dated 2000 BC, where two figures are holding curved sticks with a ball between them. Meanwhile, in the National Archaeological Museum in Athens a square marble slab dating back to 514 BC shows four sporting scenes. One of these has a group of youths playing a game that is unmistakably hockey.

In the Middle Ages hockey appears in pictures and written accounts across Europe and the first mention of the word ‘hockey’ appears in a written record of a speech made by the English King Edward III. Unfortunately for the game’s development at the time, the king was declaring a ban on hockey and “other such idle games.”

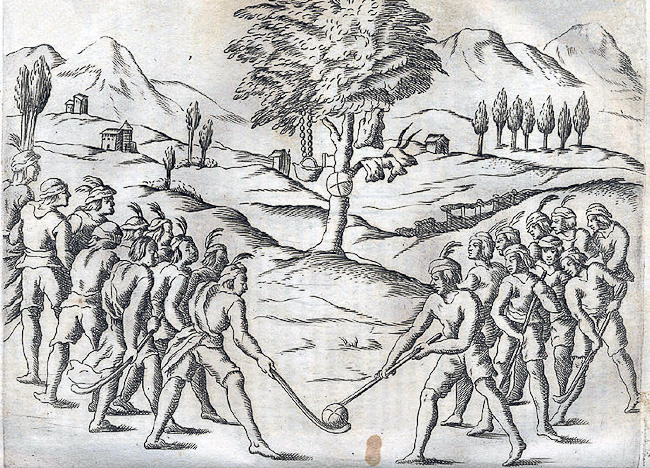

While hockey was developing in Europe with variations such as bandy in the Netherlands, hoquet in France and hurling in Ireland, in South America, the Mapuche – sometimes known as the Araucanians – tribe of Chile created their own version of the stick and ball game – palin – in the 16th century. Some confusion arises over the terminology here, as the Spanish colonisers refer to palin as “chueca”, but the games are one and the same. While palin, or cheuca, were similar in style to bandy, hoquet and other European versions, historians believe they developed independently, with no influence from the Old World. The games were uncannily similar to the modern hockey game that was formalised and codified by the English public school system two centuries later in the 18th century.

It is easy to see how hockey developed among communities. The hunters and gatherers, the communities and tribes would have relaxed by creating games. The earliest and easiest type of game is one of chase and catch, but kicking an object, throwing an object or using a stick to propel an object are all activities that are as old as humanity itself. In no time at all, it becomes one versus one, then a group versus another group and suddenly you have a game.

Most sport in the Middle Ages, up to the 19th century, served a dual purpose. The games were a form of entertainment and relaxation, but they also had a serious purpose – to keep the players fit and prepared for military action. Historical evidence suggest that the game of palin was played as a mock battle to sort disputes among the local indigenous tribes; as a ceremonial activity following a funeral; and as part of community get togethers. Certainly, despite two periods in the 17th and 18th centuries when the sport was banned for being too violent, palin was a large part of life in communities stretching across Chile, right up to the 20th century.

From the 19th century onwards, a gradual sophistication and formalisation of techniques, rules, equipment and tactics took place. While the roots of the sport lie in the ancient civilisations of the Americas, the Greek and Roman Empires and Egypt, the modern game with its rules, standardisation of kit and competitive league structure is derived from the British public school system and the spread of the British Empire in the 19th century. From the playing fields of public schools such as Eton and Windsor, the game was taken by soldiers, traders and settlers to North and South America, India, Australia and Africa, and soon it was an internationally recognised sport, warranting inclusion in the 1908 Olympics.

The modern game of hockey, which would still be recognisable to us today, first appeared in the Americas at the start of the 20th century. Constance Applebee introduced the game in the USA in 1901. She was an English physical education instructor at Harvard University and it was soon being played by women at colleges and clubs, particularly in the north-east of the States. The men took up the sport in 1928, the same year that the United States Field Hockey Association was formed. The men’s team had rapid success, winning a bronze medal at the 1932 Los Angeles Olympics.

British influence was also the driving force behind the formation of the Argentine Hockey Association (now Argentine Hockey Confederation), which was formed in 1908. British people working in Argentina at the beginning of the 20th century formed themselves, and interested local people, into clubs and the first match was played between Belgrano Athletic San Isidro (later renamed Club Atletico San Isidro - CASI) , and Pacific Railway AC (now San Martin) . Just a year later women’s clubs were permitted and the first female side to be formed was Belgrano Ladies. It wasn’t until 1983 that the Argentina Hockey Confederation was formed, but by then the women’s team in particular had already made their mark on the world stage, as runners up in the inaugural women’s World Cup in 1974 and 1976. Within a few short years, hockey in Argentina became the national sport for women and its top players were guaranteed superstar status among the population.

Canada’s position as a member of the Commonwealth made it a country ripe for hockey development. British settlers and soldiers brought the game with them and it was played in pockets of Canada throughout the early years of the 20th century. In Canada, climate and the popularity of its sister sport – ice hockey – means that field hockey has always taken a second row seat. However, the past 20 years has seen lot of hard work invested into the development of both men’s and women’s hockey and, with the men ranked 14th in the world and the women ranked 22nd, there are clear signs that the hard work is paying off.

Across the Pan-American landscape, hockey arrived gradually over the course of the 20th century. Chile continues to have a strong tradition in the sport – perhaps traceable to the influence of palin – and Uruguay, Trinidad and Tobago and Mexico are all teams that are now established on the world stage. With the advent of the Hockey World League series, these teams have serious opportunities to advance up the rankings and push for qualification for the major world hockey events in the near future. For the other teams, many still in their infancy, the pioneering work of the higher ranked nations is creating a strong hockey infrastructure and knowledge base from which teams across the PAHF will benefit.

When it comes to the global stage, the PAHF was quick to get involved. The International Hockey Federation (FIH) was formed in 1924, when seven national associations joined forces to create a structure within which international hockey could flourish. These founding nations were Austria, Belgium Czechoslovakia, France, Hungary, Spain and Switzerland. The Pan American Hockey Federation was one of the first continental associations to join the International Hockey Federation. By 1964, 51 countries had become affiliated to the FIH, alongside three continental associations – the PAHF, Africa and Asia. The federations of Europe and Oceania joined more than a decade later.

Now the Pan American Hockey Federation is the second largest federation in terms of numbers of nations. Europe leads the way, but with 17 men’s teams and 18 women’s teams, the PAHF is a growing force on the international hockey stage.